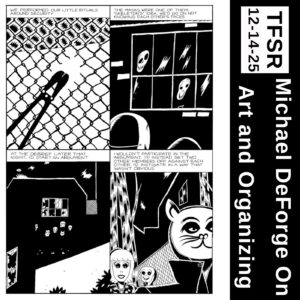

Michael DeForge

This week we’re sharing Ian’s talk with cartoonist Michael DeForge about the intersection of organizing and art. The conversation touches on Michael’s recent organizing efforts in solidarity with Mskwaasin Agnew, who was among those detained by Israel as part of the Flotilla to bring aid to Gaza. They also discuss the good and bad of instructive political stories and Michael shares details about his upcoming collection from Drawn and Quarterly, scheduled for release in early 2026.

- Bluesky: @michaeldeforge.bsky.social

- Instagram:@michaeldeforgecomics

- website:michael-deforge.com

- patreon.com/cw/michaeldeforge

- https://www.noarmsinthearts.com/

Xinachtli

But first we’re sharing an interview that Outlaw Podcast did with Jazz from the support crew for Xinachtli. Xinachtli is a Chicano anarchist who’s been serving a 50 year sentence since 1996 for aggravated assault, and now, nearly 30 years into his sentence (22 of which have been in solitary confinement according to his support website) is suffering accumulated health issues. During a collapse of his health, he was moved to the infirmary but he’s been denied any treatment, diagnosis or access to his medical care. While in infirmary, he had personal items from his cell thrown away, including his commissary card The demands for Xinachtli are simple and you can find the numbers and links in our show notes:

-

Call to put pressure for his demands on TDCJ and McCConnell unit.

-

We are asking organizations to sign our demand letter to TDCJ. Link can be found in our bio or tinyurl.com/xsupportletter

-

Join us on December 13 to protest in Austin, Texas.

-

Donate to the campaign to support legal expenses.

WHAT YOU CAN DO NO. 1: PHONE AND EMAIL BLAST

- Call the McConnell Unit to demand they give X access to commissary and his medical records IMMEDIATELY. McConnell Unit: (361) 362-2300

- Call TDCJ Health Services to demand X receive his medical records and is transfered to a hospital for treatment IMMEDIATELY.

TDCJ Health Services: (936) 437-4271- Call or email TDCJ State Classification Committee to demand they reclassify X so he can be transferred to a medical facility.

TDCJ SCC: (936) 437-6231

classify@tdcj.texas.gov

Phone blast signup: https://bit.ly/xphoneblast

If you’re on instagram, you can learn more about Xinacthli’s condition and how to get involved via his site @FreeXinacthliNow and if you can hear our conversation from 2024 with Xinacthli or a recording of him speaking about his arrest from 2010.

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Slip by Autechre from Amber

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: I am here with artist and activist, Michael DeForge, if you think that’s a fair description. Michael, can you please introduce yourself to our audience?

Michael DeForge: Yeah. My name is Michael. I use he/him pronouns. I work as a cartoonist in Toronto, and my practice involves both drawing comic books, but also different forms of commercial illustration. I also do some organizing here in Toronto. Most recently I’ve been part of the No Arms in the Arts campaign, which is a coalition of different organizations in the cultural sector that have been mobilizing against art sponsors or art institutions with ties to Israel’s genocide. Whether it’s weapons companies within Israel, weapons companies implicated in the murder of Palestinians, or companies that sponsor the arts or have ties to the arts and maintain some type of affiliations with Israel’s genocide. This includes, for instance, sponsors or organizations donating to IOF (Israeli Occupation Forces) affiliated groups, or Israeli settler groups, settler construction or illegal settlements, etc., that sort of thing.

TFSR: Thank you very much. So I reached out to you based on some social media posts from earlier this month, you and others were recently arrested for an action, and I was wondering if you could describe that for our listeners? Whatever you’re comfortable sharing.

Michael DeForge: Sure, but you know I mentioned this to you before, I have to be a little bit vague about the details, because these are charges that are still ongoing. Charges that include a number of other people who aren’t me, and so I have to be, you know, intentionally, a little bit vague, and use a lot of goofy ‘allegedly(s)’ when talking about it. But I can give at least some context.

Earlier in the month, one of the boats that was part of the wave of freedom flotillas on the way to try to break the siege on Gaza, included a boat that had five Canadian citizens out of the wave of people that were included in the Global Sumud Flotilla. There were actions in support of the Flotilla, specifically here in Toronto, with demands related to the release of one of the flotilla members who was kidnapped by Israel and held within an Israeli prison, Miss Glossin Agnew. Because she lives in Toronto, one of the alleged actions, allegedly involved an occupation protesting a member of parliament who would technically be her elected representative. This was a member of parliament named Karim Bardeesy, who is a member of the Liberal Party. The Liberal Party is currently the ruling party in Canada, and there were also demands that Canada implement an arms embargo on Israel.

Miss Glossin, I can also say, is a comrade. I can’t say I know her very well, but she does a lot of work in harm reduction circles, so I sort of know her through harm reduction work and other types of organizing I’ve been involved with. There were 19 arrests across a span of 24 hours related to actions triggered by Israel’s kidnapping of Miss Glossin and the four other Canadians who were detained by Israel and held in an Israeli prison. In the weeks since, we’ve heard all sorts of accounts about the types of treatment and torture that all the flotilla members went through, which is what those prisons specialize in because it is the type of mistreatment and torture that they subject Palestinian prisoners through on a daily basis.

So yeah, there’s a bunch of us, and we’re facing criminal charges. And because the charges are ongoing, that’s about as much as I can say about it. I did post about it on social media just because I happen to have a reading event in Buffalo (NY, USA) the next day after the arrest, and I was basically advised by a lawyer that I shouldn’t go, even though it’s sort of an ongoing criminal charge, I shouldn’t risk trying to cross the border to America just given the situation there right now. I needed to explain to the store hosting the event, the people who were hoping to come to the reading, the other artists I was reading with and so on, about why I wouldn’t be there the following evening.

TFSR: Thank you very much. Are you able to speak to Miss Glossin’s current status?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, thankfully, she is back. She’s talked a little bit about it on social media, but yeah, thankfully she is back and safe in Toronto.

TFSR: So, in general, can you talk about the response and the actions you’ve seen in Toronto organizing spaces around this genocide in Gaza, and maybe talk about how you feel the state has responded?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, there’s been, I’d say, like maybe 130 to 150 arrests. In terms of criminal charges, I would guess there’s lots of cases where one person will be charged with multiple counts. But I would guess somewhere around 150-plus criminal charges in total. Very few of them have resulted in convictions. A lot of them just get thrown out. In addition to the arrests resulting in a lot of injuries, the police violence of the arrests and the shutting down of the actions themselves, the state here has been basically going through and using these charges despite the fact that they don’t bring many criminal convictions as a way to drain the movement of resources.

So a lot of the times, you can kind of assume that the city doesn’t think anything will come of the charges, but they know it’ll be months and in some cases a year-plus, where the person being charged will be tied up in legal fees. You know, these things take a lot of time and commitment. A lot of charges are publicized in a way where it’s specifically designed to get arrestees’ names out there in a way that jeopardizes both their privacy and also, in a lot of cases, their livelihood. That’s sort of been a big part of it.

A lot of the charges come with bail conditions that do make it a lot more difficult to either organize or participate in any number of forms of civil or uncivil disobedience. For example, there’ll sometimes be non-association bail conditions or sometimes there will be bail conditions specifically prohibiting people from being in certain areas. Sometimes there are bail conditions around protests themselves. A lot of these are technically violations of Canadian Charter Rights. Not that I put a lot of credence to our Charter Rights or the state’s interest in enforcing them, but it’s just to say that it’s really a ‘punishment by process’ thing.

Around five years ago, I was criminally charged with something (the charges have been dropped, so I can talk more freely about it). It was a big instance of like a ‘punishment by process’ sort of thing, where I was part of about a dozen people charged over an action disrupting railway infrastructure in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en land defenders and we were able to beat the charges. But, of course, it just comes with being tied up in all of these other ways. At that point we had a certain set of bail conditions and we had to fight the bail conditions and go through this whole process. So it’s very common to see this with Project Resolute.

Project Resolute is the name that Toronto Police have been using to investigate anything related to Palestine whatsoever, and it’s technically under the hate crimes unit. But aside from just how racist that is, that like anything in solidarity with Gaza would be considered a potential hate crime, none of the charges or investigations that Project Resolute has carried out have actually even resulted in a hate crime charge. Which maybe speaks to just how spurious this whole operation is.

TFSR: Sure. Kind of maybe taking a broader view, it sounds to me like you have been organizing for years. Is there much overlap in your organizing circles and the circles in which you practice your artwork?

Michael DeForge: At the moment, there is more than usual, I would say. As I mentioned earlier, there’s the No Arms in the Arts campaign, but yeah, generally around Palestine, culture sector organizing has become a lot of the organizing work I’ve been doing, which hasn’t always been the case.

I’ve been in groups that have been totally unrelated to culture sector stuff, but right now I’m a member of the Toronto chapter of a group called Writers Against the War in Gaza. Which, as a group, we are members of the No Arms in the Arts Coalition. A lot of the No Arms work, as I mentioned, is specifically around arts institutions that usually have like corporate or charitable sponsors with ties to the genocide. A lot of that has been trying to move artists in a way where artists see themselves as political actors, or artists see themselves as workers, and are trying to leverage that in certain ways. I think there’s frequently an assumption that the only way artists can engage with ‘politics’ is through their art. You know, like making art about something they feel strongly about, which I think is great, people should do that, of course. But a lot of the campaign has been about how artists actually situate themselves in this broader industry and what leverage do we have in this industry?

Some questions that we frequently pose are, like in this case, about Zionist interests, or more broadly, corporate interests finding art a valuable space. The reason why there are these corporate sponsorships, or rich billionaire philanthropists sponsoring the arts. It’s not out of the good of their heart, right? Like they they’re getting something out of it. So, how do we use that against them, and what is it that they’re getting out of it? And how can we sort of push back on that and make art spaces something where we feel like we have more agency and ownership and control? So lately, I have been more involved in in organizing conversations with my peers, whether it’s filmmakers, musicians, or authors and so on.

TFSR: Can you talk a little bit about your early life and some of the formative experiences that brought you to art making, and maybe talk about if these were the same or in conjunction with the experiences that brought you to, I guess, political awareness?

Michael DeForge: In terms of art, I had always been reading comics ever since I was a kid. My parents had different comic strip collections around the house when I was growing up. So that would include the Far Side, Calvin and Hobbes, Peanuts, or Bloom County. As I got older, I got into superheroes, and then in high school and my 20s, over that course of like 10 to 15 years, I started to realize that comics were more than just superheroes or comic strips. I got into different types of comics, like I found out about Manga, found out about alternative comics, that sort of thing.

A lot of that was happening at the same time I was getting into punk and sort of DIY music circles, and saw a lot of art that included comics, but also like posters, and design that was a lot different from art I’d seen before and made in a sort of a different tradition. So like a lot of art that came out of the noise scene at the time I was a teenager, became a big influence on me, and that would include artists sort of from the Fort Thunder Scene Collective, and people just sort of more broadly associated with that, like Matt Brinkman, Brian Chippendale, etc.

In terms of politics, some of that happened around the same time, but I feel like I didn’t have any kind of one awakening. I sometimes get the “what radicalized you?” question from either interviewers or just friends, and it’s sort of funny, but it wasn’t really one thing. But I would say that punk and zines were my introduction to a lot of political ideas that I hadn’t really engaged with before.

I was raised in a pretty like milquetoast family. Like a vaguely progressive, left-liberal household. It was sort of through zines that I got introduced to different ideas and different conflicting ideas. The sort of flippant answer that I give is, “I just kept reading books until I became a communist.” But that’s actually not that far from what happened. It was a sort of a gradual thing where I’d be reading and I’d be talking to people, those people would argue with me and maybe change my mind about something. I try to put some of those politics to practice, and they’d get developed more. It’s a very gradual arc, and one that I hope isn’t over. I sort of feel like political development, ideally, is like a lifelong thing. So, yeah, I didn’t really have thunderbolt moments like I did with comics where I was like “Wow, I’ve never seen anything like this before!”, I would say with politics, it’s been more gradual.

TFSR: It sounds like you were steeped in it, in situations where it came to you through osmosis. Would you say that’s fair?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, I’d say that’s fair, like osmosis. I’d say that sort of like getting more active really put a lot of things that I had thought about in theory to… like kind of ‘when rubber hits the road’ when you’re actually in the thick of something. I feel like there’s no substitute for political education that actually comes from the really unglamorous work of trying to move people, or working on infrastructure, or being involved in and planning in direct action and all the really kind of awful, boring or excruciating stuff. I feel like that’s kind of is where I really learned the most.

TFSR: Would you say that, as far as kind of mentorship or instruction, that that mostly came from peer groups in the scene?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, I would say that, like just a lot of comrades kind of across the left political spectrum. I do think that I have benefited a lot from learning from organizers, especially who have been organizing in different contexts. I learned from the sort of generational knowledge I got from people who have been kind of in the weeds much longer than I have.

TFSR: So I follow you on social media and on on Patreon, and it seems like a lot of your recent output, in addition to comics, are flyers and posters promoting events. I understand that that has always kind of been a factor of your practice. But I was particularly struck by the series you’ve been doing on Asian Action Cinema, I think that I saw a hardboiled poster. The way that you put these together, they seem very reflexive in their composition. I was wondering if you mainly put these together, kind of off the cuff?

Michael DeForge: It kind of depends. Sometimes a poster comes together really quickly. Sometimes I go through like, 30-40 variations. And usually the stuff that seems simplest is the stuff I have to fiddle around with the most. I think when I go for a very maximalist composition, you’re just sort of filling the page so you can just trust that it’s going to be busy, it’s going to be loud, this sort of big, full, detailed drawing. But when something only has a few elements, I feel like it’s almost tougher, because you have to really nail those few elements. Where, if you have 30 different things going on in a composition, it’s it’s fine if a few of them are not exactly perfect, but yeah, I do like doing the film posters a lot.

Posters have just always been a very large part of my practice. When I started drawing, I was making zines in high school, but I was also doing a lot of gig posters. I was inspired a lot by a few specific poster artists from the punk and DIY and noise scenes at the time, and was trying to do posters myself. I had a crappy high school silk screening rig where I was like exposing screens out of a pizza box and trying to print in my closet, like, literally a closet, because it was the place where I could get pitch black. I cut my teeth learning to make posters then. And did a lot of gig posters. I still do the odd music poster, but for whatever reason, I get tapped to do music less. Now most of my posters are either for film, usually a lot of, repertory type screenings, independent cinema screenings, and political posters, like agitprop (agitation and propaganda). I like making propaganda. Like there’s a few artists in Toronto who kind of have the agitprop beat, I guess. And I would be one of them. Posters remain a big part of what I do. I think a thing that I like about it, in addition to just maybe poster art always having been a big influence on me, is it’s an excuse to try out different styles and design solutions a little bit.

You know, I think all of my posters for all purposes are very clearly recognizably done by me. But when you’re working with like a filmmaker’s vision, or you’re working with a band or something, you are having to do this thing of figuring out how, like, this can’t just be the Michael show, you know. I have to actually communicate something about this other work I’m interacting with, whether it’s like music or movie, and that’s the same with agitprop. My design preferences or aesthetic preferences are still going to come through, but in a lot of cases, they have to be secondary or at least negotiate with ‘who is this actually trying to speak to?’ You know, my inclination is always to do work that is extremely hard to read. I like illegible lettering and illegible typography, because that’s some of the scene I came out of. You see that in punk and noise and metal writing, but when you’re working on a piece of propaganda, you don’t want it to be illegible, right? You want someone to be able to to see it across the street and clock it and read it. So, yeah, I like having all of these considerations. I like thinking of design problems and design solutions. Yeah.

TFSR: Where do these things overlap, and where do they diverge? So, like, what are the differences between making a flyer and a mini comic in a book? Like, I’m sure that you have different short term goals, but I wonder, I guess, if you start from the same creative place.

Michael DeForge: It depends a little, my comics are very much their own thing. I think of my comics as very different from my commercial work. I sort of set a bit of a boundary where my comics are… like I have editors and I have a publisher right now, and I’ll take their input and I talk to them, but for the most part, I control everything in my comics. I really like that. I like controlling every aspect of the writing and the art, and as much as I can, aspects of the design. Once you get to stuff like production you start to lose control. But for the most part, I get to handle everything and just indulge all of my creative whims entirely. Yeah, I like being a control freak in that context.

For commercial work, even though I enjoy it, you know, doing posters for like an independent screening series, it’s still a work for hire gig. In those cases, I have to answer to the person who I’m working for. And then I do commercial gigs for people that I don’t always like their input. Like, usually, if I’m doing something for a screening series, it’s like someone I’m cool with, someone I know a little or whatever. Sometimes I do animation work, and the animation work has been for people I’ve worked with for a few years and really enjoy working with, but then I move on to like magazine editorial work, and sometimes I don’t really love the magazine, or I don’t really love the art director, and so on. You know, it’s just the range of freelance, and I’ve been doing it long enough that I know a little bit when to put up a fight.

You know, certainly, if it comes to me not being paid or me being mistreated in some way, I’ll put up a fight. But in terms of, like, creative decisions, I have a clearer idea of whether this is a hill to die on, or it isn’t. I’m not ultimately the guy who gets to decide something in some of these cases, and I know sometimes I just have to put put my ego aside and put out something that maybe I wouldn’t be super happy with. But luckily, I don’t get a lot of those gigs as much anymore. I get less high profile gigs than I used to anyway. Most of the freelance work I do now, thankfully (even if I kind of like the financial security of a few of the higher paying gigs I used to get) is usually like working with people where they kind of know my work already, and the reason they’re working with me is because they want to see me kind of do my thing.

I do kind of treat them as separate, but there’s obviously some bleed over. Stuff like the political propaganda, I’m not getting paid for, but it’s not exactly personal work. It exists in some weird medium, and there’s certainly lots of weird bleed that happens. But for the most part, I do separate the two.

TFSR: Okay, from the perspective of the stuff that you have total control over. Do you tend to let the project lead the way, or do you tend to go into it with with some goals?

Michael DeForge: I usually have some. You know, goals is maybe a little too lofty, but I tend to have an idea of what the shape of a project will be, and then from there I improvise a lot of the writing. So, I’ll usually have a premise in mind, and maybe the big themes, or maybe a sense of who the lead character is and maybe where I want to take them, but I try to only have a pretty rough skeleton of what I want to say or what I’m trying to do, and then give myself a lot of room to improvise. That’s the most clear in a few comics I’ve done at this point that have started out as comic strip serials, like Ant Colony, Styx, Angelica, Leaving Richards Valley, and Birds of Maine, where all have been comics I’ve done that were originally either weekly or daily strips, and in those cases, you know, I kind of had a sense of what the comic would be about.

The most recent of that set was called Birds of Maine, and it was about this like utopian bird society that lived on the moon. A lot of the planning I did was mostly just shaping some of the principles the bird society would live around, because I wanted it to be utopian, and a reflection of some of my own politics. I also really liked the Ursula Le Guin thing of an ambiguous utopia. So I didn’t want it to necessarily say it had all the answers. I just wanted to map it out a little, and then once I had this sort of shape of the world, I knew I could just elaborate on it as much as I can. So, I have these characters, and they’ll go on journeys, and I’ll need to know exactly the journey they’ll go on. If I‘m talking about utopian bird technology, and I have some idea of how it worked. You know, I made all the bird technology revolve around, like mushrooms and fungal networks and stuff. But it’s like, I don’t need to to know all of it, you know, that can come as I write.

Then even for smaller stories, like stories that are smaller in scope, it’ll be similar. Like my last book that came out earlier this year is called Holy Lacrimony, and it was about an alien abduction. It emerged from another comic idea that I ended up scrapping. I knew that the book was going to be two halves. From the start, I knew half of it was going to be the protagonist on the alien spaceship, and then the other half was going to be the protagonist in a UFO support group back on earth. I didn’t need to have all the details sorted out, I just knew that this was the structure of it, and then I could kind of trust the book to almost be like a bag. A bag I was filling until the shape formed or something. That was the worst analogy I could have given, but I sort of trusted that it would fill out.

TFSR: So I’m just kind of basing this on how much of your work seems to be in collaboration, but I get the impression that you’re an extrovert. I think that you maybe touched on this a little bit earlier, but, is making art something that you associate with being in community, or is it something that you do in private and bring into your community?

Michael DeForge: You know, it’s funny. I don’t really think of myself as particularly extroverted. I think of myself, as having tendencies that are maybe introvert tendencies. Not that I put a lot of thought into being an extrovert versus introvert, but you know, left to my own devices, I really like just working in my room alone, watching movies, listening to music, drawing comics. But I feel like all these other things in my life kind of pull me out of it, and for good reason. Because, even though my personal comfort might tend towards being alone more than I actually am, there are things that I value more than comfort, and that includes my community and the friendships and relationships I have in my community.

It also includes political commitments, you know, like a lot of the things that are kind of a part of leftist activity. Whether it’s organizing, whether it’s direct action, like whatever you might say, it’s not stuff that I am particularly inclined towards, or stuff that I necessarily feel that comfortable with or find intuitive, like conflict, whether it’s conflict with people within a circle or people outside, you know. I used to think of myself as very conflict averse, but now I just sort of am okay with it, and that just came from experience. That’s the same with, like, a lot. I don’t naturally think strategically, but I sometimes have been forced to think about strategy, same with a lot of the kind of formal and informal day to day infrastructure that is required to keep communities going, whether it’s like an arts community, or political community, or something else.

In terms of my art, it’s sort of a weird spectrum. Because sometimes it’s another thing where maybe I do divide my comics and some of my other stuff a lot more. Where my comics, I do feel like I make it on my own and then I bring it to other people, and there’s a bit of interplay with that because a lot of the time I am in conversation with other cartoonists and friends who aren’t authors or cartoonists or artists, and we’re talking about ideas a lot. I feel like that stuff makes it to the page and the work I’m doing is still in dialog with my friends, with my community, with my peers. My partner is a cartoonist, like my best friend is a cartoonist, we talk about comics all the time, and we’re always just sort of bouncing ideas off of each other. So even though I think of it as something where, like, “I’m in control, I have final say, I’m doing it alone”, all of these other things are brought into it. And that doesn’t, of course, even account for all the just day to day experiences that get brought into a work all the time.

Then there’s work where it’s really stuff that I see, like, maybe beholden or accountable to a community. So the agitprop being a big one, where it’s like, I don’t like the idea of making ‘political art’, just as like a flight of fancy, you know, like, I want it to actually be politically useful in some way. I feel like that is work that I do where I think of it as accountable to the people around me. Not like if I do something ‘bad’, they can, like, discipline me or something, but it’s more like, ‘how is this useful to people? Like, how can I be of use?’

TFSR: And in that regard, do you mean anchored to, like, a campaign or an action or something like that?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, like anchored to a campaign, or it doesn’t even have to be as formal as a campaign, necessarily. I don’t like the idea of just sort of going out on my own and doing something, if it’s not something at least I’m a little bit engaged in, or friends are engaged in. I feel like I do need to have some skin in the game, a little bit, however that might look like. I don’t really like the image of the ‘movement artist’ who is just sort of there dispensing ‘art wisdom’ at a remove. I want to feel feel useful. I do feel like it’s the responsibility of making art that way to be in communication with the communities it’s affecting or whatever it might be.

TFSR: Thank you. A bit of a digression. Here you cited Gary Larson, or Gary Larson’s Far Side, as an early interest. I wonder if those still kind of get to you. I wonder if you saw the new cartoons he put out last week?

Michael DeForge: So actually, I didn’t see the new work until you mentioned it in your email. But, like it delighted me when I did see it.

TFSR: I bring it up just kind of in regards to how it relates to a larger body of work. I wonder if you choose projects and gigs with a larger body of work in mind?

Michael DeForge: At this point, I don’t. I try to be a bit unprecious about what the larger body of work is going to look like. I don’t think I was always that way. Early on in my career, I had this idea of what a career arc could look like. Nw that I’ve been at it for so many years, I know that a lot of careers take a lot of detours, and that’s actually sometimes the more interesting thing when there are lots of detours.

In a lot of my work, I think of it as at least coming back to a lot of themes and ideas. Community comes up a lot in my work, and I have a lot of books that are almost like pairs with each other in the way that I write about community. Like Styx, Angelica, Leaving Richards Valley, and Birds of Maine are all very explicitly about my thinking through the way communities come together and sometimes break apart. Same with my new book Holy Lacrimony. Then I also have a lot of work that I think of as, like comics that are more about being stuck in my own head, and I’m talking about my own experience with mental illness and institutionalization. I have a lot of work that like pairs that way. And work that’s about technology, like work that’s critiquing technology, A Familiar Face and Birds of Maine are both sort of a dystopian and utopian vision of technological development that I think of as like a mirror in certain ways.

On the whole, you can see me coming back to these ideas from different vantage points, and visual ideas too. Hopefully with a slightly different perspective each time. But in terms of this whole respectable body of work, I don’t tend to think about it too much. A lot of my favorite artists, and that includes cartoonists, but it also includes filmmakers or musicians, are ones who’ve worked in a lot of different formats and a lot of different genres across a lot of different tones. I always find that very interesting, and the work that I’m most excited about, even if it’s artists where that includes some amount of failure. Or like projects that kind of miss the mark, or sort of silly throwaway things. I really like artists who are ambitious in that way, in terms of comics.

I think Gilbert Hernandez is maybe, I think the ultimate for that. Like, both Hernandez brothers are great for that. But Gilbert has done so much work that is something you could point to as like, this is a literary comic you could pass to someone in a bookstore, you could put it in the book review section of a reputable newspaper, and it could win a bunch of literary prizes. Then he’ll do another comic that is like as bizarre and abstract and aggressive as like something that would be incomprehensible to that same audience. Then he’ll do something that’s like a goofy sci-fi pastiche, or he’ll do stuff that’s like straight up porn, and it all kind of fits in this larger Gilbert universe.

But clearly if he was someone who really cared about catering to one market, he wouldn’t be taking all the zigs and zags that he does. That would be a much less interesting body of work if it was all the one thing. He would do great at just the one thing. And that extends to a lot of like… I think of Johnny Toe as a filmmaker who I really love, who has worked in a lot of different genres and tones. Or, like Prince has been a huge thing in my life since I was a kid. I love Prince. When you look at Prince’s body of work, I think now, since he’s passed, there’s more of an appreciation for eras of his career that at the time people thought of as like, huge missteps for him, you know. A thing I always appreciated is that he was unafraid to take really big and weird swings throughout his career. So yeah, those are the sorts of bodies of work that I tend to be most attracted to.

TFSR: Would you say that Gilbert speaks to you a little bit more on more a deeper level than Jaime does?

Michael DeForge: Ugh, that’s tough, like both of them I love so much, and they’re so part of, like, my DNA, and just the DNA of comics. But, I’d say Gilbert is weird in a way that I think is closer to how I approach art. Because like Jaime has been been such a big influence. I think if you look at the DNA of my work, you will see more Gilbert than Jaime, even though both of them have been huge for me. Because Jaime has taken a lot of similar swings, but like, especially recently, some of the most recent Gilbert comics are like, so weird. I was thinking about how hard it’d be to explain to somebody just like what this book is about. Like, it’d be so difficult, but I love that, you know, it makes me so happy for how bracing they are. Some of the work, I’m almost like, he’s antagonizing the reader, which delights me.

TFSR: Have you had a chance to meet them?

Michael DeForge: Yeah, both of them are just the nicest guys you’ll ever meet. Both have been extremely generous, supportive, and kind to me. Especially really early on in my career, I was really, you know, like “these guys are living legends”, so the fact that they gave me the time of day meant a lot. I know they do the same for a lot of young cartoonists, so they are like just the best.

TFSR: Awesome. So I want to talk a little bit briefly as we kind of start to wind down. A lot of your past work, I feel touches on the ecological through a lens of the societal, whether that’s natural ecology in works like Spotting Deer or the utopias you mentioned in Birds of Maine. Is there an ecological factor in your upcoming work? I wonder what you are able to share, if anything about All the Cameras in My Room, coming out in 2026 from Drawn and Quarterly?

Michael DeForge: It won’t be as big a factor in All the Cameras in My Room, but I have two projects on the go where that is a part of it again. For All the Cameras in My Room, it’s a collection of short stories, and it ended up being a pretty dystopian collection. I’d say like half the stories are engaging in mass culture in a certain way, sometimes in a critical way, sometimes just in a very silly way. Then the other half are very concerned with surveillance and performance. The anchoring comic is a short story that is the longest story in the collection. I’d say it’s about 60 pages, where everything else is probably 10 to 20 pages. It’s a comic about someone who has infiltrated a leftist group on behalf of an unnamed law enforcement agency. So it’s like I would say a little bit more on the pessimistic side. I have sometimes alternated between utopian comics and pessimistic comics.

My last short story collection, Heaven No Hell, I’d say was a bit of intentionally a bit of a mix, because I have heaven and hell in the title, both in the title, but I would say, like it leaned towards the optimistic side. I tried to kind of have a lot of grace notes in that collection. And this one, I don’t think I have much of that. I think it’s a much bleaker comic. So I don’t know what that says about me or my outlook or the world, but that’s where that one is at.

In terms of ecology and nature, it is something I keep coming back to. I specifically think sometimes we have this idea that nature is something separate from us, or nature is something separate from technology, or nature is something separate from a ‘man made world’. But the thing I have come back to in a lot of my comics, is basically “no, for better or worse and often times worse we’re in it,” you know, if we’re in a city, we are in nature, so act accordingly. Figure out ways to look at those divisions, or break down those divisions. So, if there was one sort of overarching thing that would bind those comics together, it’d be that idea.

TFSR: You know, in kind of looking at your work, it seems like the art and the politics kind of inform each other and kind of feed into each other. I wonder, and maybe this is probably too vague of a question, I can maybe hone in on a little bit. But what role do you feel culture plays in putting forth politics? And what do you feel are the limitations there? There was a piece today in New Republic about protesters in Nepal and Madagascar using the One Piece anime and manga Jolly Roger flag as a symbol of their struggle. I just wonder what you make of stuff like that?

Michael DeForge: I mean, when I see stuff like that, it’s cool, you know. But I also know to some extent when stuff is popular, people are going to kind of rally around it in ways that you can’t really predict. Like there’s been mass culture work that I’ve thought of as outright reactionary, that has been used in like, you know, leftist or liberatory movements. I didn’t think the politics of the Joker movie were particularly good. I thought it leaned towards either like the reactionary or the incoherent, but you know you could see liberatory movements adopt that imagery.

Then at the other end of the spectrum, The Matrix, and the Wachowski sisters whose politics are pretty explicit. I would argue that The Matrix’s politics, and certainly their politics as two trans women are pretty explicit. But, not by any fault of their own, the concept of the red pill is, like, predominantly used by reactionary groups that, like, stand for everything they are against, very explicitly against. So there’s just like an amount that’s kind of like hard to control, right?

I think it’s cool when I see that. Certainly mass culture is able to shape what people see. I think there are ways sometimes mass culture can be a bit of a temperature check on what conventional wisdoms might be. And then ways that mass culture shapes what people’s political horizons might seem like, you know? Like what might be politically possible, but within that, it’s sort of like hard to predict. I think a lot of the times too, culture, not just mass culture, gets used as a containment strategy and gets used as a way to either placate, or co-opt, or defame, whether it’s radical ideas or radical movements, and that’s something I grapple with a lot in my practice.

If you’re only ever engaging with things on the culture side, it’s very easy for the ruling class to kind of like, defame different types of dissent, or neutralize it, while still keeping the dissent there. Because they factored in all of the artistic forms of dissent. They’ve factored in the stand up comedians making jokes. You can see that, not just in mass culture, but you can go to like some of the biggest museums in the world, and they will be honoring and commemorating the same protest movements that 10 years ago, 15 years ago, 50 years ago, they had a hand in criminalizing. If they were still around and active today, the museums would still have a hand in criminalizing them.

I think it’s important, and movements need artwork. That’s extremely important. Movements need artwork and creativity. I try to be very aware of the limits of that, and the dangers of only ever engaging with some of these ideas on the cultural production side.

TFSR: So in this upcoming book, you mentioned that one of the stories is about a leftist group that is being infiltrated. What signifiers did you kind of give that group, to make it explicit to the reader, what that group represents?

Michael DeForge: I tried to not make it like, here’s the exact type of anarchist they are, or here’s the exact type of communist they are, you know, or here’s the adjective that precedes them. But the types of actions they engage in, I try to make it at least a little bit explicit. This is like a very common thing that gets talked about, like the way in left spaces you can act like a cop without being a cop. That was kind one of the ideas I was trying to engage with the most. The slippages we have in our language, the slippages we have in our behavior, and how that stuff implicates us in all of these ways. I’ll say it’s supposed to be like a little satirical, maybe not like a joke a minute, but it’s supposed to be a little bit funny and be a bit about how these spaces can sometimes self sabotage themselves, and doesn’t only kind of need the infiltrator to push things along. There’s obviously, like, a ton of literature and a ton of zines about this, right.

TFSR: As a working artist based in Canada, especially, you know, as you pursue work in America, I wonder if you have anything that you might offer about the role of socialized health care that you receive in Canada, if it’s been helpful in in pursuing your art?

Michael DeForge: I mean, absolutely it has been. You know, there’s sometimes this thing like, when you’re Canadian and you’re talking to Americans, it’s default to insist, like, “hey, Canada’s awful, I know it’s not as bad as America.” But the socialized medicine, is huge. It’s been something where even as bad as things get, we do have like a higher bare minimum. That is a higher bare minimum that’s not unique to Canada, right? Like the states is, in many ways, one of the odd men out, in that it doesn’t think of healthcare as like a basic, irreducible minimum.

It’s allowed me to make comics. I still have to worry about my health, and there’s very dire economic consequences to me getting sick, but still having that as a safety net has been big. Another big thing too is that there are still arts grants in Canada. They’re getting cut and it’s like they’re in danger constantly, they’re shrinking every year. I know there are grants in the States, but there are less. But like, there are municipal, provincial and federal arts grants in Canada, and they’ve been ones that I’ve been able to receive in the past. There’s a lot of things like that where it has made working as an artist here much, much easier than if I had the exact same career arc, but had it south of the border.

TFSR: Okay, Michael, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me. I really appreciate it.

Michael DeForge: Oh, thank you. Thanks for having me.